“Would you like us to create our own surgical robot?” doctor Nawrat asked professor Religa. “When will I be able to use it to operate?” replied professor. That was how Robin Heart came into being

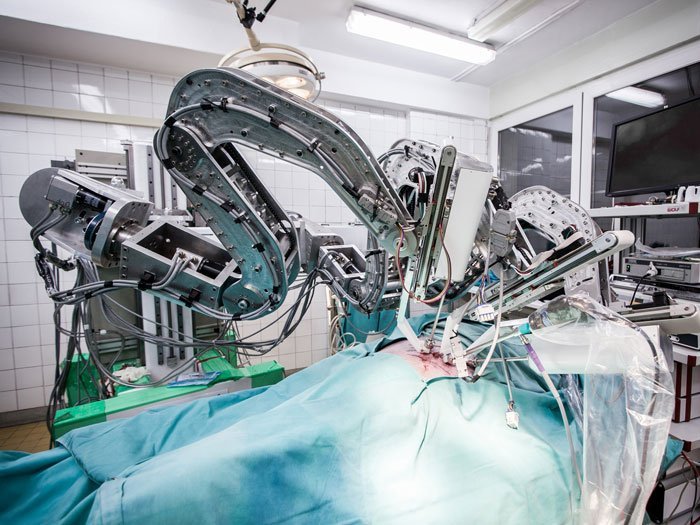

First, there was Robin Heart 1 with an independent base. Today’s Robin Heart PVA is fixed to the laboratory operating table and has two arms. But the Heart Prostheses Institute in Zabrze has also developed other Robins, including Robin HeartVision capable of controlling the endoscope, Tele Robin Heart fitted with an original tool platform and the Robin Heart Shell surgeon control console, as well as Robin Heart mc2, which is the biggest three-arm robot that can substitute two surgeons and an assistant responsible for controlling the endoscope orientation.

“Here is Robin Heart, the first surgical robot designed for heart operations,” doctor Zbigniew Nawrat, the director of the Institute, presents his “mechanical child”.

“Why would anyone need robots in cardiac surgery?” I ask.

“Cardiac surgeons are most convenient if they can operate on a patient whose chest is fully opened. If that condition is met, they can get closer to the patient to see more clearly what they are doing by precisely controlling their hands. However, this is the most invasive way to operate, so whenever possible non-invasive surgical procedures are performed. After cutting small holes in the patient’s body, a surgeon inserts an endoscope, i.e. a tool with a camera, which shows the operated area inside the body. The surgeon then performs the operation with the use of long mechanical endoscopic tools. Obviously, that results in the surgeon being physically farther away from the body and changes entirely the way he or she has to work. The surgeon can no longer feel the interaction with the tissue and can no longer directly see the operated area. This means that surgeons cannot be as precise as they would be in the case of standard operations with the patient’s chest opened. Robots allow for the highest level of precision while reducing the invasiveness of surgical treatments.”

Da Vinci, or robots in medicine

The benefits of using surgical robots in medicine are enormous: patients lose little blood, there are fewer complications, the operations are shorter, the scars are smaller, the operation requires less staff, operations can be performed remotely, and patients are discharged from the hospital much earlier.

That is why every year hospitals acquire an increasing number of such machines. Although surgical robots technologies have been developed in Italy, Germany, UK, China, France, the Netherlands and Poland, it is Da Vinci, an expensive but popular American robot used mostly in urology and gynecology, that reigns supreme on the market. Globally, five thousand Da Vinci robots perform one million operations every year. The first Da Vinci in Poland appeared in 2010. It was the first surgical robot we purchased. In 2018 Polish hospitals had five robots of that type which performed 60 surgical procedures. In 2019 their number increased to eight and the number of operations with their use soared to 900.

According to the report “Surgical robotics market in Poland 2019. Forecast for 2020-2023.” developed by Upper Finance and PMR, there is one Da Vinci robot per 100 thousand inhabitants in the USA, with only one robot of that kind per 800 thousand and per 6.5 million inhabitants in Europe and in Poland respectively. Germany has 130 thousand Da Vinci systems. Poland has eight. As estimated by Karolina Kroczek, one of Zbigniew Nawrat’s doctoral students, Poland needs over 30 robots of that sort to keep up with the European standards.

Revolution for a song

What was the origin of the name “Robin Heart”?

“The name came from “rob in heart” or “a robot in the heart”, because the machine is a robot designed for assisting in heart operations,” explains doctor Nawrat. “But I also liked the associations with Robin Hood. The robot was meant to be cheap and accessible to everyone, as opposed to expensive Da Vinci.

You have to pay a lot not only for the Da Vinci machine itself but also for its maintenance. Besides, it cannot be used for everything; it is mostly used for gynecological and urological operations.”

“We started from what was the most difficult: from the heart,” says doctor Nawrat. “It has been 10 years since we tested our robots in three experimental operations on animals. The three procedures included the gallbladder, heart valve and coronary heart disease operations. We have about a dozen of prototypes. Our Robin Heart mc2 is currently the biggest surgical robot in the world.

Unfortunately, none of Robins has ever been produced on a large scale. What we have at our disposal are just trial versions. We have managed to commercialize only Robin HeartPortVisionAble PVA (the simplest, lightweight, portable robot used to control endoscopic vision). The license for that robot was sold by the institute last year.”

“If we had money, we would have put our own Polish surgical robot to use 10 years ago!”, Nawrat sounds both rueful and irritated. “Over the past 20 years we have spent less on the works on the Polish robot than what you need to buy one Da Vinci. With a smaller amount of money we have been able to create an entirely new field and have taught people in Poland to think about robots. We have managed to hold conferences, publish journals, establish departments and institutes of robotics. I really don’t know what else I can do…”

What’s above what’s below

How did it happen that specialists from Zabrze started working on prototypes of world’s best surgical robots? According to doctor Nawrat, it was all by accident. It was all about professor Religa.

“After he came to Silesia, he has changed my life entirely,” smiles Nawrat. “Originally, I specialized in theoretical physics. I was fascinated with the idea of grasping everything: what’s above and what’s below, both on a nano and macroscale. I was growing up in the belief that soon we would understand everything and that we would be able to use it to our advantage. But when I heard that professor Religa was creating the Artificial Heart Laboratory in Zabrze, I decided to contact Romek Kustosz, who managed the project, and asked him if they needed my help. It was 1988. The talk I held with then reader Religa was short but, as you can see, it resulted in long-term collaboration. At the beginning, me and Romek Kustosz were assigned a special task: to create a Polish artificial heart. Later, we focused on establishing the Foundation of Cardiac Surgery Development, the institute, the laboratories, we took on other research projects …

The American heart Religa saw during his internship in the USA cost one million dollars, which was much more than Polish specialists could afford back in the People’s Republic of Poland. In 1985, in Zabrze, professor Religa performed the first successful heart transplant procedure. Since then the number of people waiting for that kind of operation started to grow fast. We needed to create a pump that would keep patients alive for as many months as needed until they could be operated.

A round-the-clock job

The pump created by Nawrat (physicist), Stolarzewicz (chemist) and Kustosz (electronic engineer) was implanted for the first time in 1993.

“It was a great experience for me. I followed the patient with my stethoscope as if I was a doctor and I listened to the sound the pump made. I just wanted to know if everything was all right. Once a theoretician, I now could see the results of my work in practice, I could help people. That was amazing!”

After joining the Religa’s team, Nawrot thought he would deal with calculations. After all, he was a theoretical physicist.

“But Religa wanted us to know the patients. We were not guests in the clinic. We were a part of the team. I spent thousands of hours with patients, checking if POLVAD ventricular assist devices were working properly. It was a round-the-clock job. Christmas Day, 1st of May, it didn’t matter. We were always there to make sure everything was OK. That was the price of being a partner to the best cardiac surgeon in Poland.

Youtube movie URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4REWjxkJUjw

Working with doctors and patients was inspiring. They asked to develop a system that would advise doctors how to treat each of the patients. Basing on diagnostic images and other data, they developed, in collaboration with Zbigniew Małota, the first Polish system to simulate computer assisted operations. The system allows to predict the hemodynamic effect of heart operations.

“Then I came up with an idea: whenever you run a simulation, you provide data to a doctor,” says doctor Nawrat enthusiastically. “And what if we moved the doctor away from the operating table and put a robot in between the doctor and the patient? We could feed the computer with all the information we have learned from the simulations. It would be possible for the doctor to remotely control the operation.

“Would you like us to create our own surgical robot?” Nawrat asked Religa.

“When will I be able to use it to operate?” asked Religa.

Everybody wanted to shake our hands

Professor Religa seemed to be the only one who believed the project could be successful. But Nawrat was confident – that was the future of medicine. He formed a team composed of specialists from several universities, including Silesian University of Technology, Warsaw University of Technology and Lodz University of Technology.

“We were doing extremely well, everybody was working on all cylinders,” he recalls. “The lights in the rooms of the Foundation of Cardiac Surgery Development were always on. There was always someone there.”

After three years they created a robot whose mobility was similar to Da Vinci’s. They came up with a completely new construction idea, they developed three control methods. Back then, they patented a dozen of solutions.

But then financial problems started and the whole team broke up. Actually, that happened four times. Despite decision-makers shaking their hands to congratulate them on their achievements, no well-thought-out investment plan was even on the horizon.

“To make things worse, we fell into a trap resulting from the regulations of the National Center for Research and Development. In order to be subsidized, you needed an industrial partner. And your own contribution. And because of the fact that in Poland no one has produced robots, we have been blocked for several years.”

Intelligence is not good enough

Doctor Nawrat points out that there will always be a lot of uncertainties in medicine.

“Humans are more complicated than outer space,” he says. – Today, we know more about the stars than about what’s inside our neighbor’s head. It will never be possible to create a full theory regarding a particular disease; you will always have to adapt it based on your experience. That is why medicine needs a system that would learn all the time; it needs artificial intelligence,” claims doctor Nawrat. “The less invasive surgery becomes and the farther away from the operating table a surgeon can stand, the bigger the role of artificial intelligence will be in supporting a doctor in making decisions and performing tasks. A surgeon will work in a console having access to reality and containing information on diagnostics and operation planning. X-ray or ultrasound imaging will show doctors where calcification is present, while simulations will suggest the best operation method for each of the cases. Artificial intelligence will analyze pieces of information and images and provide a doctor with the ones that are necessary at a given time.”

However, being interested in AI, people forget that to understand the world you need theory. Artificial intelligence is just emanation of our own intelligence.

“There is a fundamental difference between intelligence and reasoning,” notices Nawrat. “Whoever observes a sample under an electron microscope can understand that the world is made of atoms based only on their intelligence. However, to figure out the same, like Democritus did, basing only on your own conclusions, requires reasoning. Reasoning is an ability to turn what we see into abstract objects. It is also working on such objects to obtain a result that could then be compared with the reality to see if it fits there.”

Why hasn’t there been a Nobel prize for AI?

“We allow AI to act on its own but we don’t understand why AI will prefer one decision over another. Watson computer is capable of correctly diagnosing one or two oncological diseases by analyzing thousands of pieces of data. And, in that respect, it is not more efficient than a good doctor. Its diagnoses must reviewed and corrected by a team of doctors on a constant basis. For that reason, some hospitals decided to get rid of Watson and IBM had to fire some members of its team.”

According to Nawrat, it is not possible to solve a problem by throwing data into a black box. We lack an idea, i.e. theory. We are not going to create any theory by mindlessly analyzing a set of information. And that is why no one has ever been awarded a Nobel prize in the field of artificial intelligence. Although artificial intelligence tells us something, we do not understand what it is. We don’t know what’s inside.

“It’s as if we threw everything we have in the fridge into a pot,” he explains. “Is that enough to prepare a meal? Yes. Is the meal going to be good? If we train the cooking system by rewarding it for tastiness, we will probably be able to make it better over time. Nonetheless, with no recipe, with no theory, we won’t know how to prepare a good meal. If a good cook doesn’t have a necessary product, he or she can prepare a different but similar meal without that product. In that sense, AI is a system that cannot be fixed. The learning process must start from scratch.”

Being apologetic all the time

Despite a multitude of problems, the Robin’s team refuse to give up. They are working on the details. They are focused on force-feedback, which is necessary to improve the precision during operations. Whenever doctors deal with a tissue, they want to receive information on whether the tissue is soft or hard and on whether they have come across calcification or thickening. For that reason, the tips of the tools created by the team of doctor Nawrat are fitted with force and signal transmission sensors with which information is transferred to the movement actuator held by the surgeon. The surgeon can “feel” if they touch a bone or soft tissue. That feature is not available anywhere else in the world. They are improving the so-called movement actuator, which is one of the best in Europe, and working on the operation planning methods. They have the first virtual operating theater in Poland.

“And we are still waiting for our Robin Heart robots to finally serve people. Surgeons keep asking me about when it will be possible to use our robots. And I still have to be apologetic.” Tomorrow perhaps? Today, we can clearly see that transferring the results of medical treatment and improving medical procedures is one of the most important challenges for humanity. If we want the humankind to survive, we have to rely on the robots.

Przeczytaj polską wersję tego tekstu TUTAJ